Jul 19, 2016 | Leadership, Transition & Change

In 2011, the Meyer Foundation and CompassPoint Nonprofit Services produced a research report “Daring to Lead” that surveyed 3,000 nonprofit executive directors and revealed a forecast of significant impending workplace transitions, with 67% of executives reporting that they expect to leave their jobs over the next five years.

Today, while we see many leadership transitions occurring among the Baby Boomer population, “what was once characterized as a pipeline problem can now be described as a bottleneck, as many individuals are choosing to work beyond the traditional retirement age due to a variety of reasons, including a prolonged economic recession,” reports the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation in “Moving Arts Leadership Forward.”

This reality requires organizations to examine its greatest asset – its people, their roles, and career paths – in strategic and creative ways. Workplaces can expect a robust boomer presence through at least 2034, when the youngest boomers will turn 70. This reality impacts Gen X-ers and Millennials aspiring to executive positions, where the wait time for succession is often longer than they would like.

While there was once a question of whether there were enough capable professionals to succeed an organization, now the challenge is more focused on developing and retaining early- and mid-career professionals in an environment of limited opportunities for formal advancement.

While not alone, nonprofits as a sector have considerable challenges in addressing this leadership reality, as they:

– Tend to be small-to-medium size operations and, as a result, are not likely to have as many resources to address strategy, planning, and leadership development.

– Are often institutions with a culture of group decision making, where business gets done through committees and boards of directors – a process that can create added delays and complexity.

– Can be highly funder-dependent, and any transition – especially with an organization’s top leadership – can threaten these vital relationships and the very future of the organization itself.

– Frequently are lead by an original founder or long-time executive. Over time, the top leader and the organization itself are inextricably connected. When this leader goes away, so could the organization.

– Often do not have sufficient reserves (if any at all) to weather an economic downturn, exposing the organization to significant financial vulnerabilities. Leadership transitions and professional development of its people, if not handled properly, can further intensify this situation.

– Sometimes have boards of directors who are unprepared to handle the transition and select and support new leaders. Despite over a decade of attention to this issue, executives and boards are still reluctant to talk proactively about succession, with just 17% reporting that their organizations had a written succession plan.

We must not overlook these pivotal leadership priorities for the development opportunities that they are. Properly and proactively managed, these changes and transitions provide an organization a period to pause, reflect, regroup, and focus. It’s a unique opportunity to examine strategic direction, priorities, and chart a future course. The key is not merely to endure it, but to emerge stronger and more dynamic from it.

You may be interested in these related blog posts:

Executive Leadership Transition and Organization Preparedness

Succession Planning: Conversation Avoided

About Jeanie Duncan: Jeanie is President of Raven Consulting Group, a business she founded that focuses on organizational change and leadership development in the nonprofit sector. She is a senior consultant for Raffa, a national firm working with nonprofit clients to lead efforts in sustainability and succession planning, executive transition and search. Additionally, Jeanie serves as adjunct faculty for the Center for Creative Leadership, a top-ranked, global provider of executive leadership education.

About Jeanie Duncan: Jeanie is President of Raven Consulting Group, a business she founded that focuses on organizational change and leadership development in the nonprofit sector. She is a senior consultant for Raffa, a national firm working with nonprofit clients to lead efforts in sustainability and succession planning, executive transition and search. Additionally, Jeanie serves as adjunct faculty for the Center for Creative Leadership, a top-ranked, global provider of executive leadership education.

Jul 10, 2016 | Succession Planning, Transition & Change

Change – sometimes surprisingly fast change – remains the one constant we can count on. Despite this, many organizations fail to prepare for the most predictable change of all…the departure of their chief executive or other key leaders. Success in leadership transitions is dependent upon readying the organization and its people for change. So, why are executive directors and boards reluctant to talk proactively about succession planning?

First of all, change is hard. In many ways, succession planning is like estate planning. People don’t like doing wills, but they know they’re important, and a real priority. Being proactive and taking advantage of advanced planning puts the executive director and board of directors in the driver’s seat to make plans and decisions in the best interest of the organization and its people, not leaving it to others or to be handled during crisis.

In examining the tendency for avoidance, it’s helpful to look at different perspectives:

Executive Director:

– If the top leader takes the subject of succession planning to the board chair, how will he or she be perceived? Is suggesting that an organization discuss leadership transition a sign of weakness? Will the board think the executive is leaving? Burned out? Less confident? Somehow less capable to effectively lead the organization? Will it plant the thought in the board’s mind that another leader would be better?

– Especially true of founders and long-time executives, there’s a great sense of pride and ownership in leading an organization. Making the decision to retire or move on to another opportunity isn’t an easy decision: “I’ve built this institution. What happens to it if I’m no longer at the helm?” Leaders who helped shape an organization often find it difficult to imagine a next step that is as compelling.

– Many hesitate to bring it up because dealing with the day-to-day work is hard enough to handle, let alone trying to plan for something often considered so future-oriented. There’s an overwhelming inclination to just wait and address the issue when it happens.

Board of Directors:

– If a member or committee of the board broaches the subject of succession planning, will it threaten the current executive director? Will the executive perceive the conversation to suggest a problem with his or her leadership?

– As a board member, one “signs up” for a specific duty. While a member may understand and respect the need for succession planning, he or she may simply not want to take on that task. “Why bring more work on myself?”

Obviously transitions raise a long list of issues that point to the complexity and difficulty of such pivotal moments. While there are no simple solutions, changes in leadership can be addressed positively and proactively and strengthen the organization as a result.

It can be helpful to examine succession planning in the broader context of executive transition management. The range of work can be short- and/or long-term planning, at a minimum ensuring that there’s an emergency plan if an executive director is suddenly unable to perform his or her duties. If an organization is lead by a founder or long-tenured director, it makes sense to have a conversation about continuity and legacy beyond the executive. And unlike a traditional search process, executive transition management helps organizations prepare for leadership succession, months, even years before the actual transition takes place, coupling the search and recruitment process with a more comprehensive range of organizational planning and leadership development services.

Despite anxiety and hesitancy in approaching the topic of succession, the positive outcomes of thoughtful conversation and transition planning far outweigh potential negative affects.

Read these other related blog posts:

Leadership Transition and Organization Preparedness

Challenges to Addressing Leadership Transition

About Jeanie Duncan: Jeanie is President of Raven Consulting Group, a business she founded that focuses on organizational change and leadership development in the nonprofit sector. She is a senior consultant for Raffa, a national firm working with nonprofit clients to lead efforts in sustainability and succession planning, executive transition and search. Additionally, Jeanie serves as adjunct faculty for the Center for Creative Leadership, a top-ranked, global provider of executive leadership education.

About Jeanie Duncan: Jeanie is President of Raven Consulting Group, a business she founded that focuses on organizational change and leadership development in the nonprofit sector. She is a senior consultant for Raffa, a national firm working with nonprofit clients to lead efforts in sustainability and succession planning, executive transition and search. Additionally, Jeanie serves as adjunct faculty for the Center for Creative Leadership, a top-ranked, global provider of executive leadership education.

Jun 17, 2016 | Transition & Change

In 2011, the Meyer Foundation and CompassPoint Nonprofit Services produced a research report “Daring to Lead” that surveyed 3,000 nonprofit executive directors and revealed a forecast of significant impending workplace transitions, with 67% of executives reporting that they expect to leave their jobs over the next five years.

Today, while we see many leadership transitions occurring among the Baby Boomer population, “what was once characterized as a pipeline problem can now be described as a bottleneck, as many individuals are choosing to work beyond the traditional retirement age due to a variety of reasons, including a prolonged economic recession,” reports the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation in “Moving Arts Leadership Forward.”

This reality requires organizations to examine its greatest asset – its people, their roles, and career paths – in strategic and creative ways. Workplaces can expect a robust boomer presence through at least 2034, when the youngest boomers will turn 70. This reality impacts Gen X-ers and Millennials aspiring to executive positions, where the wait time for succession is often longer than they would like.

While there was once a question of whether there were enough capable professionals to succeed an organization, now the challenge is more focused on developing and retaining early- and mid-career professionals in an environment of limited opportunities for formal advancement.

Obviously transitions raise a long list of issues that point to the complexity and difficulty of such pivotal moments. While there are no simple solutions, changes in leadership can be addressed positively and proactively and strengthen the organization as a result.

– At a minimum, an organization should have an emergency transition/succession plan if an Executive Director is suddenly unable to perform his or her duties. Many boards of directors are underprepared to handle the transition and selection and support of new leaders, with just 17% reporting that their organizations have a written succession plan (per Daring to Lead 2011).

– Often, nonprofit institutions have a culture of group decision-making – a process that can be complex and create delays. A board can address this issue in its bylaws, empowering a small representative group (executive or personnel committee, for example) to act on its behalf – in situations like this and others.

– Have written job descriptions and a performance evaluation system in place for all staff. This is especially critical for the Executive Director position. Board leadership should have familiarity of the Executive’s core role and functions and how well the individual is performing against agreed upon goals.

– Institute a culture of ongoing cross training among staff, whereby individuals have a clear understanding of one another’s responsibilities – especially among the leadership team.

– If possible, an organization’s key donor relationships should be shared by the Executive Director and other members of the staff and board. This helps lessen vulnerability, share fund raising responsibility, and ensure that vital donor relationships are held with the organization and not exclusively with a particular leader.

– Nonprofit groups often do not have sufficient reserves to weather significant challenges, exposing the organization to financial vulnerabilities. Leadership transitions, if not handled properly, can intensify this situation. However, advanced planning and good management allows even the smallest organizations to build a few months’ operating reserve.

These strategies are critical to developing leaders and preparing for both short- and long-term transitions. In the case of a longer-term planned departure, these actions can be coupled with broader assessment and planning, presenting an organization with a unique opportunity to examine strategic direction, priorities, and chart a future course. The key is not merely to endure transitions, but to emerge stronger and more dynamic from it.

You may also be interested in these related blog posts:

Succession Planning: Conversation Avoided

Challenges to Addressing Leadership Transitions

About Jeanie Duncan: Jeanie is President of Raven Consulting Group, a business she founded that focuses on organizational change and leadership development in the nonprofit sector. She is a senior consultant for Raffa, a national firm working with nonprofit clients to lead efforts in sustainability and succession planning, executive transition and search. Additionally, Jeanie serves as adjunct faculty for the Center for Creative Leadership, a top-ranked, global provider of executive leadership education.

About Jeanie Duncan: Jeanie is President of Raven Consulting Group, a business she founded that focuses on organizational change and leadership development in the nonprofit sector. She is a senior consultant for Raffa, a national firm working with nonprofit clients to lead efforts in sustainability and succession planning, executive transition and search. Additionally, Jeanie serves as adjunct faculty for the Center for Creative Leadership, a top-ranked, global provider of executive leadership education.

Feb 10, 2015 | Leadership

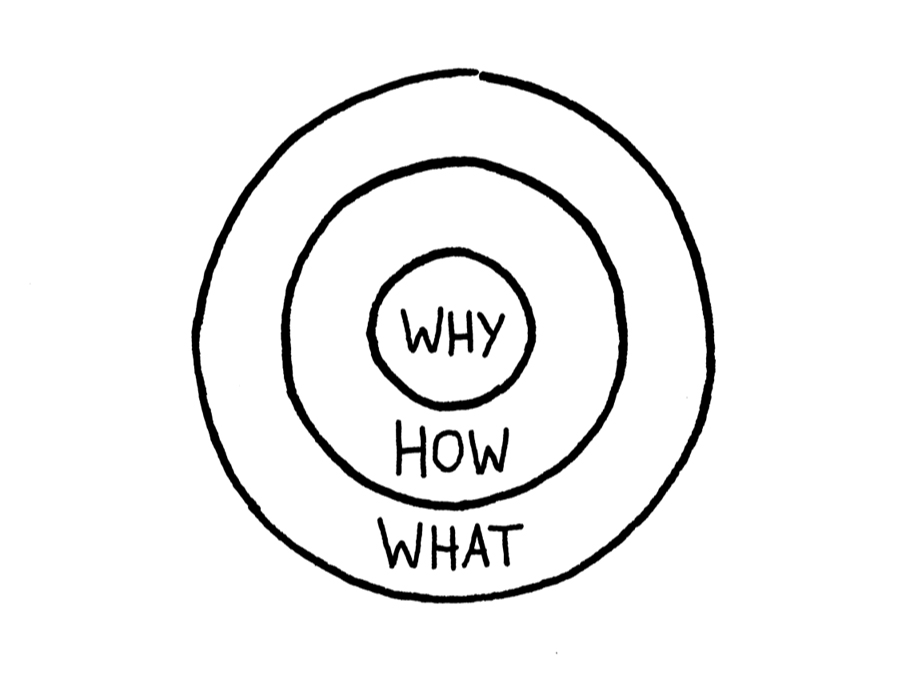

I recently completed some forecasting and goal setting for my business. As I went through this process, I pulled from several resources that inspire and motivate me, a favorite of which is Simon Sinek’s “Start With WHY.” He expresses his message through what he calls The Golden Circle:

His premise is that you must begin with your WHY, and from there figure out your HOW and WHAT. When Sinek studied successful leaders, he found a common denominator – they inspire through a clearly and passionately articulated WHY. They hold their WHY front and center – like a North Star – to guide their WHAT and HOW. Everything emerges from the core WHY, or belief. HOWs are the actions they take to realize that belief. And WHATs are the results of those actions.

I’ve known about Sinek’s philosophy for a while, but I find even greater meaning in it now – not only for my own personal and business reflection, but also for my clients.

According to this line of thought, most every person and organization knows WHAT they do. That’s usually pretty clear. Some know HOW they do it. But very few know WHY they do WHAT they do. Or at least they don’t stop to think about it or articulate it frequently and consistently.

By WHY, Sinek doesn’t mean ‘to earn revenue,’ but rather, he’s referring to your purpose, your cause, your belief. Sinek asks, “WHAT makes you get out of bed in the morning? WHY do you care? And WHY should others care?” Think of it as communicating from the inside out.

Think for a moment – We busily go about our day-to-day. We take on roles, assignments, projects, and business…and before long we’ve amassed this huge volume of ‘stuff’ without pausing to think about WHY we’re doing it. Even if we know our WHY, we can fail to consciously use it as our lens or filter for making decisions.

As I went through my own reflection, I see room for getting clearer with my own “WHY” and doing a better job of sharing my story.

A theme for me over my life is that I’m a self-starter and risk taker. I grew up in an entrepreneurial family with my parents owning two businesses. My siblings and I were involved in those businesses where there was no task too great or small; we all pitched in to get it done. And if we didn’t know how to do it, we figured it out. Failures were acknowledged as just one step closer to succeeding.

When I finished college, my first jobs were new positions where I was responsible for creating the role. Later on, I set my vision and sites for what I wanted and set out to achieve it, including starting my own business. Through it all, I didn’t have all the information, the guidelines were ambiguous, and I needed to perform and produce results fast. I quite like this messiness – stepping into the unknown, bringing order to chaos, and charting a course where there isn’t one.

This pattern and energy shapes my WHY – To help people know WHAT they want, find their courage, step forward, and take risks. This is the path to which my life and my work is devoted.

Sinek offers, “People don’t buy WHAT you do. They buy WHY you do it. People don’t buy WHAT you sell. They buy WHAT you believe. And people follow you not because they have to, not because they are paid to, but because they want to.”

This concept comes alive every day in business:

- Strategy Development: For an organization to develop its goals, strategies, and tactics, it must first be crystal clear on its WHY, often presented most succinct in a well-crafted vision and mission. As Sinek offers, “It’s not just WHAT or HOW you do things that matters; what matters more is that your WHAT and HOW is consistent with your WHY.” With a WHY clearly stated in an organization, anyone within the organization can make a decision as clearly and as accurately as the top leader.

- Sustainability Planning: The products and services offered by many organizations are broad and complex. It’s important to critically and regularly examine these lines of business and ask, “WHY do we do this,” looking at both mission impact and financial return to gauge long-term sustainability. Yet, we can get so caught up in the day-to-day, that our WHAT mutates into a complex web without a clear connection to vision and mission, and with limited (or lost) return on investment.

- Succession Planning and Leadership Transitions: Sinek concludes that top executives are successful in great part because they inspire and embody what they believe. When the person who personifies the WHY departs without clearly articulating WHY the company was founded in the first place, they leave no clear cause for their successor to lead. “Successful succession is more than selecting someone with an appropriate skill set – it’s about finding someone who is in lockstep with the original cause around which the business was founded. Great 2nd and 3rd CEOs don’t take the helm to implement their own vision of the future; they pick up the original banner and lead the company into the next generation.”

I encourage you to get to your WHY. It yields greater confidence than ‘I think it’s right.’ It’s more scalable than ‘I feel it’s right.’ When you know your WHY, the highest level of assurance you can offer is, ‘I know it’s right.’

_______

Sinek, S. (2009). Start with why: how great leaders inspire everyone to take action. New York: Penguin Group.

About Jeanie Duncan: Jeanie is President of Raven Consulting Group, a business she founded that focuses on organizational change and leadership development in the nonprofit sector. She is a senior consultant for Raffa, a national firm working with nonprofit clients to lead efforts in sustainability and succession planning, executive transition and search. Additionally, Jeanie serves as adjunct faculty for the Center for Creative Leadership, a top-ranked, global provider of executive leadership education.

About Jeanie Duncan: Jeanie is President of Raven Consulting Group, a business she founded that focuses on organizational change and leadership development in the nonprofit sector. She is a senior consultant for Raffa, a national firm working with nonprofit clients to lead efforts in sustainability and succession planning, executive transition and search. Additionally, Jeanie serves as adjunct faculty for the Center for Creative Leadership, a top-ranked, global provider of executive leadership education.

About Jeanie Duncan: Jeanie is President of Raven Consulting Group, a business she founded that focuses on organizational change and leadership development in the nonprofit sector. She is a senior consultant for Raffa, a national firm working with nonprofit clients to lead efforts in sustainability and succession planning, executive transition and search. Additionally, Jeanie serves as adjunct faculty for the Center for Creative Leadership, a top-ranked, global provider of executive leadership education.

About Jeanie Duncan: Jeanie is President of Raven Consulting Group, a business she founded that focuses on organizational change and leadership development in the nonprofit sector. She is a senior consultant for Raffa, a national firm working with nonprofit clients to lead efforts in sustainability and succession planning, executive transition and search. Additionally, Jeanie serves as adjunct faculty for the Center for Creative Leadership, a top-ranked, global provider of executive leadership education.